- India

- International

Explained: The idea of regional Supreme Court Benches, and ‘divisions’ of the top court

It is obvious that travelling to New Delhi or engaging expensive Supreme Court counsel to pursue a case is beyond the means of most litigants. Standing Committees of Parliament recommended in 2004, 2005, and 2006 that Benches of the court be set up elsewhere.

Supreme Court Rules give the Chief Justice of India the power to constitute Benches — he can, for instance, have a Constitution Bench of seven judges in New Delhi, and set up smaller Benches in, say, four or six places across the country.

Supreme Court Rules give the Chief Justice of India the power to constitute Benches — he can, for instance, have a Constitution Bench of seven judges in New Delhi, and set up smaller Benches in, say, four or six places across the country.

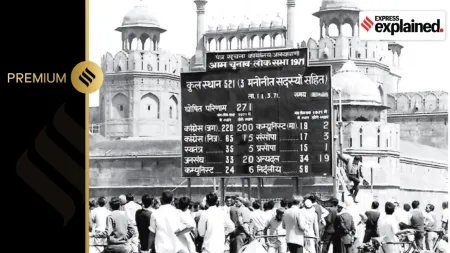

Vice-President M Venkaiah Naidu has suggested that the Supreme Court institute four regional Benches to tackle the enormous backlog of cases, and to ensure their speedy disposal. Naidu also endorsed the recommendation of the Law Commission of India that the top court should be split into two divisions. These ideas are not new; apart from the Law Commission, they were mooted also in the Congress manifesto for this year’s Lok Sabha elections. But they have not developed into a serious debate, and the Supreme Court itself has been opposed to these ideas. The Vice-President on Friday spoke in the presence of present and former Supreme Court Justices and several prominent legal personalities.

The problem of pendency of cases

The world’s first constitutional courts were set up in Europe — in Austria in 1920 and in Germany after World War II. Today, 55 countries have constitutional courts, including most European or civil law jurisdictions. In the early decades of the Republic, the Supreme Court of India, too, functioned largely as a constitutional court, with some 70-80 judgments being delivered every year by Constitution Benches of five or more judges who ruled, as per Article 145(3) of the Constitution, on matters “involving a substantial question of law as to the interpretation of [the] Constitution”. This number has now come down to 10-12. Due to their heavy workload, judges mostly sit in two- or three-judge Benches to dispose of all kinds of cases; these include several non-Constitutional and relatively petty matters such as bans (or lifting of bans) on films, or allegations that a Commissioner of Police is misusing his powers. On some occasions, even PILs on demands such as Sardar jokes should be banned, or that Muslims should be sent out of the country, come before the Supreme Court. This heavy workload is due to the fact that India’s Supreme Court is perhaps the world’s most powerful court, with a very wide jurisdiction. It hears matters between the Centre and states, and between two or more states; rules on civil and criminal appeals; and advises the President on questions of law and fact. On the question of violation of fundamental rights, anyone can approach the Supreme Court directly. The result: more than 65,000 cases are pending in the Supreme Court, and disposal of appeals takes many years. Several cases involving the interpretation of the Constitution by five or seven judges have been pending for years.

What the Law Commission said

Back in March 1984, the Tenth Law Commission of India (95th Report) under Justice K K Mathew recommended that “the Supreme Court of India should consist of two Divisions, namely (a) Constitutional Division, and (b) Legal Division”, and that “only matters of Constitutional law may be assigned to the proposed Constitutional Division”. The Eleventh Law Commission under the chairmanship of Justice D A Desai (125th Report, 1988) “reiterate(d) that the recommendation for splitting the (Supreme) Court into two halves deserves to be implemented”. Thereafter, the Eighteenth Law Commission under Justice A R Lakshmanan (229th Report, 2009) recommended that “a Constitution Bench be set up at Delhi to deal with constitutional and other allied issues”, and “four Cassation Benches be set up in the Northern region/zone at Delhi, the Southern region/zone at Chennai/Hyderabad, the Eastern region/zone at Kolkata and the Western region/zone at Mumbai to deal with all appellate work arising out of the orders/judgments of the High Courts of the particular region”. Indeed, many countries around the world have Courts of Cassation that decide cases involving non-Constitutional disputes and appeals from the lower level of courts. These are courts of last resort that have the power to reverse decisions of lower courts. (Cassation: annulment, cancellation, reversal)

Argument for multiple Benches

It has been pointed out that Article 39A says that “the state shall secure that the operation of the legal system promotes justice, on a basis of equal opportunity, and shall… ensure that opportunities for securing justice are not denied to any citizen by reason of economic or other disabilities”. It is obvious that travelling to New Delhi or engaging expensive Supreme Court counsel to pursue a case is beyond the means of most litigants. Standing Committees of Parliament recommended in 2004, 2005, and 2006 that Benches of the court be set up elsewhere. In 2008, the Committee suggested that at least one Bench be set up on a trial basis in Chennai. But the Supreme Court has not agreed with the proposal, which in its opinion will dilute the prestige of the court. Article 130 says that “the Supreme Court shall sit in Delhi or in such other place or places, as the Chief Justice of India may, with the approval of the President, from time to time, appoint.” Supreme Court Rules give the Chief Justice of India the power to constitute Benches — he can, for instance, have a Constitution Bench of seven judges in New Delhi, and set up smaller Benches in, say, four or six places across the country.

More Explained

EXPRESS OPINION

May 01: Latest News

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05